Dual polyhedron

In geometry, polyhedra are associated into pairs called duals, where the vertices of one correspond to the faces of the other. The dual of the dual is the original polyhedron. The dual of a polyhedron with equivalent vertices is one with equivalent faces, and of one with equivalent edges is another with equivalent edges. So the regular polyhedra — the Platonic solids and Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra — are arranged into dual pairs, with the exception of the regular tetrahedron which is self-dual.

Duality is also sometimes called reciprocity or polarity.

Contents |

Kinds of duality

There are many kinds of duality. The kinds most relevant to polyhedra are:

- Polar reciprocity

- Topological duality

- Abstract duality

Polar reciprocation

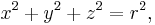

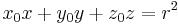

Duality is most commonly defined in terms of polar reciprocation about a concentric sphere. Here, each vertex (pole) is associated with a face plane (polar plane or just polar) so that the ray from the center to the vertex is perpendicular to the plane, and the product of the distances from the center to each is equal to the square of the radius. In coordinates, for reciprocation about the sphere

the vertex

is associated with the plane

.

.

The vertices of the dual, then, are the poles reciprocal to the face planes of the original, and the faces of the dual lie in the polars reciprocal to the vertices of the original. Also, any two adjacent vertices define an edge, and these will reciprocate to two adjacent faces which intersect to define an edge of the dual.

Notice that the exact form of the dual will depend on what sphere we reciprocate with respect to; as we move the sphere around, the dual form distorts. The choice of center (of the sphere) is sufficient to define the dual up to similarity. If multiple symmetry axes are present, they will necessarily intersect at a single point, and this is usually taken to be the center. Failing that a circumscribed sphere, inscribed sphere, or midsphere (one with all edges as tangents) can be used.

If a polyhedron has an element passing through the center of the sphere, the corresponding element of its dual will go to infinity. Since traditional "Euclidean" space never reaches infinity, the projective equivalent, called extended Euclidean space, must be formed by adding the required 'plane at infinity'. Some theorists prefer to stick to Euclidean space and say that there is no dual. Meanwhile Wenninger (1983) found a way to represent these infinite duals, in a manner suitable for making models (of some finite portion!).

The concept of duality here is closely related to the duality in projective geometry, where lines and edges are interchanged; in fact it is often mistakenly taken to be a particular version of the same. Projective polarity works well enough for convex polyhedra. But for non-convex figures such as star polyhedra, when we seek to rigorously define this form of polyhedral duality in terms of projective polarity, various problems appear. See for example Grünbaum & Shepherd (1988), and Gailiunas & Sharp (2005). Wenninger (1983) also discusses some issues on the way to deriving his infinite duals.

Canonical duals

Any convex polyhedron can be distorted into a canonical form, in which a midsphere (or intersphere) exists tangent to every edge, such that the average position of these points is the center of the sphere, and this form is unique up to congruences.

If we reciprocate such a polyhedron about its intersphere, the dual polyhedron will share the same edge-tangency points and so must also be canonical; it is the canonical dual, and the two together form a canonical dual compound.

Topological duality

We can distort a dual polyhedron such that it can no longer be obtained by reciprocating the original in any sphere; in this case we can say that the two polyhedra are still topologically dual.

It is worth noting that the vertices and edges of a convex polyhedron can be projected to form a graph (sometimes called a Schlegel diagram) on the sphere or on a flat plane, and the corresponding graph formed by the dual of this polyhedron is its dual graph.

Abstract duality

An abstract polyhedron is a certain kind of partially ordered set (poset) of elements, such that adjacencies, or connections, between elements of the set correspond to adjacencies between elements (faces, edges, etc.) of a polyhedron. Such a poset may be represented in a Hasse diagram. Any such poset has a dual poset. The Hasse diagram of the dual polyhedron is obtained very simply, by turning the original diagram upside-down.

Dorman Luke construction

For a uniform polyhedron, the face of the dual polyhedron may be found from the original polyhedron's vertex figure using the Dorman Luke construction. This construction was originally described by Cundy & Rollett (1961) and later generalised by Wenninger (1983).

As an example, here is the vertex figure (red) of the cuboctahedron being used to derive a face (blue) of the rhombic dodecahedron.

Before beginning the construction, the vertex figure ABCD is (in this case) obtained by cutting each connected edge at its mid-point.

Dorman Luke's construction then proceeds:

-

- Draw the circumcircle (tangent to every corner).

- Draw lines tangent to the circumcircle at each corner A, B, C, D.

- Mark the points E, F, G, H, where each line meets the adjacent line.

- The polygon EFGH is a face of the dual polyhedron.

The size of the vertex figure was chosen so that its circumcircle lies on the intersphere of the cuboctahedron, which also becomes the intersphere of the dual rhombic dodecahedron.

Dorman Luke's construction can only be used where a polyhedron has such an intersphere and the vertex figure is cyclic, i.e. for uniform polyhedra.

Self-dual polyhedra

A self-dual polyhedron is a polyhedron whose dual is a congruent figure, though not necessarily the identical figure: for example, the dual of a regular tetrahedron is a regular tetrahedron "facing the opposite direction" (reflected through the origin).

A self-dual polyhedron must have the same number of vertices as faces. We can distinguish between structural (topological) duality and geometrical duality. The topological structure of a self-dual polyhedron is also self-dual. Whether or not such a polyhedron is also geometrically self-dual will depend on the particular geometrical duality being considered. For example, every polygon is topologically self-dual (it has the same number of vertices as edges, and these are switched by duality), but will not in general be geometrically self-dual (up to rigid motion, for instance) – regular polygons are geometrically self-dual (all angles are congruent, as are all edges, so under duality these congruences swap), but irregular polygons may not be geometrically self-dual.

The most common geometric arrangement is where some convex polyhedron is in its canonical form, which is to say that the all its edges must be tangent to a certain sphere whose centre coincides with the centre of gravity (average position) of the tangent points. If the polar reciprocal of the canonical form in the sphere is congruent to the original, then the figure is self-dual.

There are infinitely many self-dual polyhedra. The simplest infinite family are the pyramids of n sides and of canonical form. Another infinite family consists of polyhedra that can be roughly described as a pyramid sitting on top of a prism (with the same number of sides). Add a frustum (pyramid with the top cut off) below the prism and you get another infinite family, and so on.

There are many other convex, self-dual polyhedra. For example, there are 6 different ones with 7 vertices, and 16 with 8 vertices.

Non-convex self-dual polyhedra can also be found, for example there is one among the facettings of the regular dodecahedron (and hence by duality also among the stellations of the icosahedron).

Tetrahedron |

Square pyramid |

Pentagonal pyramid |

Hexagonal pyramid |

Elongated triangular pyramid |

Elongated square pyramid |

Elongated pentagonal pyramid |

Self dual compound polyhedra

The Stella octangula, being a compound of two tetrahedra is also self-dual, as well as four other regular-dual compounds.

Dual polytopes and tessellations

Duality can be generalized to n-dimensional space and dual polytopes; in 2-dimensions these are called dual polygons.

The vertices of one polytope correspond to the (n − 1)-dimensional elements, or facets, of the other, and the j points that define a (j − 1)-dimensional element will correspond to j hyperplanes that intersect to give a (n − j)-dimensional element. The dual of a honeycomb can be defined similarly.

In general, the facets of a polytope's dual will be the topological duals of the polytope's vertex figures. For regular and uniform polytopes, the dual facets will be the polar reciprocals of the original's facets. For example, in four dimensions, the vertex figure of the 600-cell is the icosahedron; the dual of the 600-cell is the 120-cell, whose facets are dodecahedra, which are the dual of the icosahedron.

Self-dual polytopes and tessellations

The primary class of self-dual polytopes are regular polytopes with palindromic Schläfli symbols. All regular polygons, {a} are self-dual, polyhedra of the form {a,a}, 4-polytopes of the form {a,b,a}, 5-polytopes of the form {a,b,b,a}, etc.

The self-dual regular polytopes are:

- All regular polygons, {a}.

- All regular n-simplexes, {3,3,...,3}

- The regular 24-cell in 4 dimensions, {3,4,3}.

- All regular n-dimensional cubic honeycombs, {4,3,...,3,4}. These may be treated as infinite polytopes.

See also

References

- H.M. Cundy & A.P. Rollett, Mathematical models, Oxford University Press (1961).

- Wenninger, Magnus (1983). Dual Models. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54325-8.

- B. Grünbaum & G. Shephard, Duality of polyhedra, Shaping space – a polyhedral approach, ed. Senechal and Fleck, Birkhäuser (1988), pp. 205–211.

- P. Gailiunas & J. Sharp, Duality of polyhedra, Internat. journ. of math. ed. in science and technology, Vol. 36, No. 6 (2005), pp. 617–642.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Dual polyhedron" from MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Dual tessellation" from MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Self-dual polyhedron" from MathWorld.

- Olshevsky, George, Duality at Glossary for Hyperspace.

- Software for displaying duals

- The Uniform Polyhedra

- Virtual Reality Polyhedra The Encyclopedia of Polyhedra